Language

How can I write a good report?

When you write a study assignment, the language must be of the right level of formality, and the content must be clearly formulated. It is no good if you use spoken language, for example, or an informal style similar to that of emails or text messages. The language must be factual and precise, and you must, of course, demonstrate that you can apply the key concepts of your profession. Moreover, it's crucial that you keep to the general rules of spelling, and that you demonstrate a common thread throughout your assignment.

The common thread

How do I establish a "common thread" in my assignment?

Your assignment must be seen as a whole, with a logical connection between the different sections and chapters. In other words: There must be a common thread.

There are several things you can do to establish a common thread. First of all, it is about your assignment having a targeted focus and a natural progression. You should never leave your reader in any doubt as to why s/he should read a specific section, or how this section should help answer the problem formulation. The sections must cohere, and the progression must be logical to the reader.

A good way to do this is to use so-called meta text. In short, meta text is text about the text. That is, text that describes what the text is about and what it is used for.

Meta text is often used at the beginning and at the end of a section. At the beginning of the section, meta text sets the frame for the section, i.e. what the section is to be used for, and what content the reader can expect to meet. At the end of the section, meta text is often used to connect the section with the rest of the assignment or to tell the reader what comes next.

Meta text at the beginning of the section

Example 1: In the following section, I will briefly outline the general concepts of experience economy.

Example 2: To answer the second part of my problem formulation, this section includes a description of what is meant by the concept of outsourcing, and a brief description of the development in Denmark for the past 10 years.

Meta text at the end of the section

Example: After having explained the technical construction of green roofs, I will look into the maintenance of the roofs in the following section.

By means of meta text you create consistency and help your reader on the way. Always remember that your reader is not as well informed as you are. Give him/her a guided and easy-to-follow experience.

Academic language

The language of a study assignment

When writing a study assignment, the language has to be clear and precise, and you must prove that you are able to apply the terminology of your profession.

Good (and not so good) words

Some words are good at demonstrating an academic approach:

Analyse, argue, justify, vary, investigate, define, discuss, assess, select.

Stay away from words that are emotional and subjective (personal):

Agitate, review, expect, feel, believe, entertain, postulate, experience, confess.

Passive and active constructions

Unfortunately, some students tend to use passive constructions (where the sender is left out) and obscure language – in the belief that it sounds more academic. However, it often confuses the reader as it is difficult to follow the reasoning and purpose of the assignment.

Take a look at this passive sentence:

The productivity of the machine is tested, and the results are passed on.

Here, you do not know who is investigating the machine's productivity or who is receiving the results. Instead, try to make the language more active and concrete:

The operator tests the productivity of the machine and forwards the results to the manufacturer.

In this sentence, it is quite clear who does the testing and who receives the results.

Keep it professional

Besides being professional and precise, the assignment must not appear personal or have a personal tone. But does this mean that you cannot write “I” in a study assignment? Not necessarily.

You may use “I” when you are taking a position on the assignment's defined problem. For example, you may use “I” about the choices you have made, the way you have chosen to structure your assignment, or when you are discussing your results:

"I have chosen to use questionnaires to uncover the preferences of my target group.”

"To answer my problem formulation, I will start by accounting for the main concepts within social media marketing and then (...)”

However, it is important that you do not use “I” in connection with think, believe or similar expressions.

"I think teenagers spend too much time on social media.”

“I think it is strange that teenagers should spend so much time on social media.”

If you are in doubt, it is always a good idea to ask your teacher what s/he prefers.

Argumentation technique

How do I argue in assignments?

When writing assignments during your studies, it is obviously important that you have control over how you argue. If you don’t familiarize yourself with how to present your points of view, you might, in the worst case, fill your assignment with undocumented claims, which is an absolute no-go! You must always be able to account for the claims you make in your assignment—in other words, you need to master the art of argumentation!

-

Basic model for argumentation technique

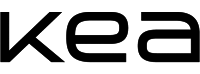

According to Toulmin, you can break down your argument into three main components: claim, grounds, and warrant

Grounds: the evidence or reasoning that supports your claim

Claim: what you want to convince your audience of

Warrant: the connection between the claim and the grounds

These three components must always be present for something to qualify as an argument. For instance, if you try to convince your audience of a point of view (claim) without explaining why (grounds), it won’t hold. It’s definitely hard to persuade people without giving them a good reason.

Claim without grounds (also called an assertion):

Electric cars are better for the environment than gasoline cars!

Claim with grounds:

Electric cars are better for the environment than gasoline cars – because they emit less CO2

The last part of Toulmin’s argumentation model—what is called the warrant—deals with the connection between the claim and the grounds. This is the shared understanding between the sender and the receiver that makes the argument acceptable. In the case of the electric car, the warrant would look something like this: The less CO2 that is emitted, the better it is for the environment.

Note that for an argument to truly work, both the sender and the receiver need to share the same understanding of the warrant. In the electric car example, most people would (by now) probably agree that reducing CO2 in the atmosphere is beneficial, but if you were to encounter someone who doesn’t share that assumption, the argument would naturally be less well-received.

It is therefore always important to consider who your audience is when you are arguing.

When you write during your studies, you are writing within an community, and you should therefore familiarize yourself with the understandings that apply there (methods, concepts, etc.).

Usually, the warrant remains implicit in the argument, as we saw in the above example with electric cars. However, in assignments, it is often a good idea to make the warrant explicit (explaining why):”We need to recude our CO2 emissions because failing to do so could have major consequences for the environment. Electric cars are therefore much better for the environment than gasoline cars, because they emit less CO2”

Even if you include all the fundamental elements in your arguments, it is equally important that you argue in a proper and objective manner. Therefore, your argumentation should of course adhere to the frameworks prescribed by your subject. This means that your argumentation must obviously be rational, professional, and grounded—not personal, subjective, or emotionally charged.

-

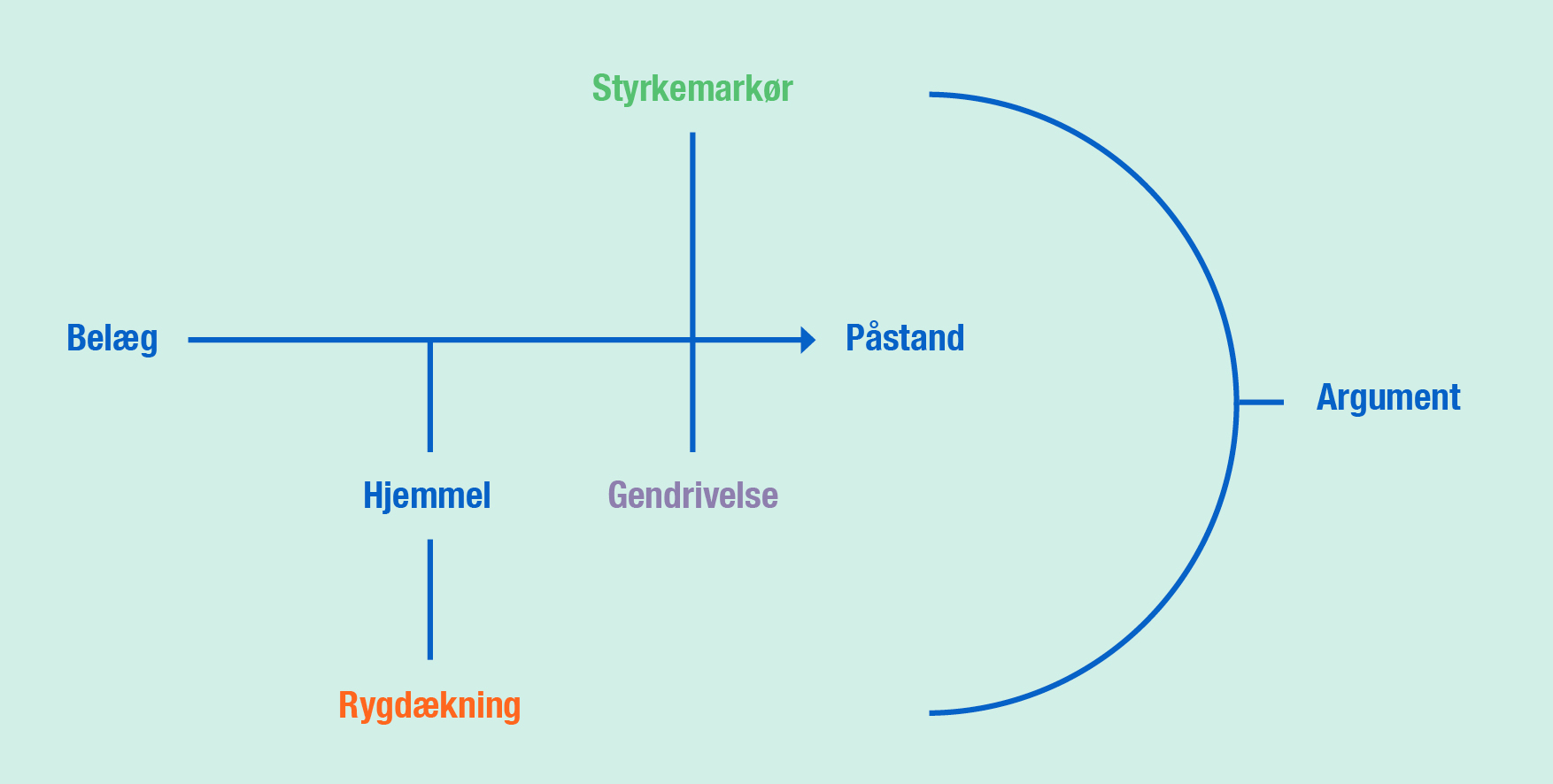

Extended model for argumentation technique

Arguments come in various sizes and levels of complexity. According to Toulmin, you can strengthen or refine your argument by adding several elements, namely: backing, qualifiers, and rebuttals.

Rebuttal: In academic assignments, it is crucial to identify areas where your argumentation might be questioned. This is achieved by using a rebuttal. You should highlight under which circumstances your argument does not hold water and explain why you still choose that solution or approach in your assignment. By doing so, you create transparency and nuance in your work and show that you are capable of critically reflecting on both yourself and your academic choices within the assignment.

Backing: You must also ensure valid backing for your argument and warrant. Essentially, you need to make sure your warrant is sufficiently substantiated. This can be achieved by including relevant backing, which could be theories, methods, or studies.

Qualifier: It is also important to consider your qualifier. Is your argument, for example, 'certain' or merely 'likely'? Argumentation often involves weighing different pieces of evidence against each other, so in most fields, it is not a weakness in an argument to avoid rigidly sticking to a single argument. On the contrary, just like with rebuttals, it can be important to emphasize that there may be both advantages and disadvantages to the solutions you have chosen.

Always consider whether your argumentation has sufficient rebuttals and backing and whether you have chosen the appropriate qualifier for your argument in context.

Example: Electric cares are likely better for the environment than gasoline cars, because they emit less CO2. However, this requires that consumers, after investing in an electric car, stick with it for a long time and not replace it after just a few years. Since the production of electric cars "costs" more CO2 than traditional gasoline cars, they must be driven for several years on the roads before it can be said that they are more environmentally friendly than gasoline cars (Albright, 2020).